Division Street

Delmont and Rafael had the most fun with this set. It's some of their favorite material, so — inevitably, according to Del — "The Early Times came out a little too early at times." Microphones were abused, and a certain amount of stumbling about and other forms of carelessness also ensued.

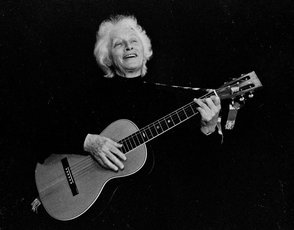

Del was never much of a crooner, anyway, preferring from an early age to hide behind his guitar and let it do the singing for him. These selections might be illustrative of his uncle Leon's contention that no matter how bad it is today, it can always get worse tomorrow.

Here it is, anyway, rough edges and all — what Dave Eggers, who interviewed Fullerton for Might magazine in the nineties, might term a work of several staggering geniuses.

Songs on this page:

Del was never much of a crooner, anyway, preferring from an early age to hide behind his guitar and let it do the singing for him. These selections might be illustrative of his uncle Leon's contention that no matter how bad it is today, it can always get worse tomorrow.

Here it is, anyway, rough edges and all — what Dave Eggers, who interviewed Fullerton for Might magazine in the nineties, might term a work of several staggering geniuses.

Songs on this page:

- Just Like Tom Joad's Blues

- Sorry For Me

- Stolen Riviera

- She's Driving Him Out of Her Mind

- The Lawrence Factory

- Never Going Back Again

- This Is the Road

- Division Street

- The Mud Creek Moan

- Laika's Lament

- Cora, Cora

- Dakota

|

1. Just Like Tom Joad's Blues

copyright Leon Fullerton The only home you’ve known is gone,

vanished in the dust. You thought the Oklahoma dirt was one thing you could trust. The highway teems with pilgrims once your neighbors and your friends. Another chapter closes, but the story never ends. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’ve got enough provisions to get you ‘cross the plain, to keep this old truck running just takes two hands and a brain. You can keep your family by you Lord only knows how long. You never were too lucky, but you were always plenty strong. You’re gonna.... The few, they live like pharaohs, the many build their tombs, monuments to hungry pride, heirless, empty rooms. You wander in the desert now, but you shall build again, the power in you vested by decree of mice and men. You’re gonna.... |

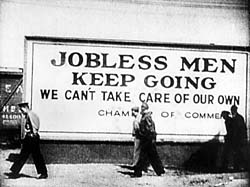

In 1940, in the company of Pete Seger, Woody Guthrie saw the movie made from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and rushed out of the theater to find a typewriter (a twentieth century apparatus combining the functions of a keyboard and printer while circumventing the added expenses and complications of computer literacy and electricity).

Guthrie stayed up all night typing, singing, and strumming, aided and abetted by half a gallon of cheap, non-union California wine. The first time he heard the song, a young and unforgivably cocky Fullerton said to friends that that’s just how it sounded — “Like it was written by a boozed-up sleep-walker.” Fullerton wrote a letter to Guthrie upon hearing the song. “Sleep-writing and you are a match made elsewhere than in heaven, Woodrow. I’ve enclosed what I humbly consider to be a tune that hits the nail a little squarer on the head.” He included the lyrics and accompanying guitar chords in the body of the letter. But he never recorded or named the song. The Fullertons, who frequently use it as a set-closer or encore, gave it the title by which it appears here - a nod both Tom Joad and Tom Thumb, Steinbeck and Dylan characters, a Fullerton double hat-tip to Guthrie and his best-known disciple. Not surprisingly, music critics disagree with Fullerton’s estimation of the Guthrie song. “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” which appears on Dust Bowl Ballads (Vanguard) is universally considered a masterwork by American music folklorists. Guthrie, however, was not offended by the young upstart’s dismissal. He promptly wrote back to Fullerton: “Keep kickin’ up the dust, kid. That’s how they make mountains.” Under Guthrie’s signature is a drawing of a little boy in oversized coveralls and twenty-gallon hat kicking dust onto a dust pile three times his height. A slingshot sticks out of his back pocket. An older, wiser Leon Fullerton later conceded to biographer Rex Geronimo that a dustbowl refugee like Guthrie was undoubtedly an expert on the subject of dust. |

|

2. Sorry For Me

copyright Leon Fullerton Gambled away my money,

cheated away my wives, lost track of where I've been and where I'm going, yes, I’ve lived a fretful life. Did hard time for some unnamed friends till the good Lord set me free - so doncha feel just a little bit sorry for me? Hey, baby, feel just a little bit sorry for me. I’ve been up, I’ve been down, I’ve been side by side, I’ve been rich, I’ve been poor, I’ve let a few things slide. You play the hand that you’ve been dealt: it’s fold or raise or see - so come on baby, feel just a little bit sorry for me. Yeah, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. When I come knocking at your back door with a hobo’s howdy-do, here but for the grace of God stands a man who’s just like you. It takes a down-by-the-riverside sanctified soul to endue such misery, so come on, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. Hey, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. Doncha feel just a little bit sorry? Doncha feel just a little bit sorry? Come on, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. |

Whenever he was in Cleveland, Fullerton liked to look up his friend Dale “Blue” Barnett and scout out a card game. The games were always for table stakes: when someone was out of money, he was out of the game. Occasionally, a player who’d lost everything would have to be ejected forcibly. One night, during an after-hours game at a bowling alley, a cleaned-out player had to be thrown out into a snow storm. The alley owner tossed out the player, followed by his coat, followed by his hat, followed by a spittoon.

The last words Fullerton heard the man shout before the owner slammed and locked the door were, “Hey! Doncha feel just a little bit sorry for me?" Fullerton himself was ejected shortly thereafter. |

|

3. Stolen Riviera

copyright Leon Fullerton She was born in a desert town,

never ran with the pack. One day she stole a preacher’s car, oh, she never looked back. Some days are bright as Mojave skies, some days drown her in ocean light, some days drown her in happiness -- I hear she’s doing alright. Folks used to say: “That girl ought to find a boy and settle down, that girl’s too wild for her own damn good, that girl keeps a silver dollar in her pocket, that girl will never learn to do the way she know she should.” She learned to praise the savior in that Buick’s back seat. Jesus jumped like a hula doll, her education to complete. The preacher’d say, “Trust the Lord and the invisible hand." He said, "I’m drowning in this sea of sand. Throw me rope, I’m a family man!” Folks used to say: "That girl.... So she left this town in the spring of aught-two, never said goodbye - had no one much to say it to. She left that Buick on a pier with a thank-you note wrapped around a silver dollar, and then she caught the last boat. Folks used to say: “That girl.... "That girl...." >>Out-take: An earlier rehearsal, featuring Ray on mandolin. |

A drunk named Harry picked young Fullerton up hitch-hiking from Oakland to Reno in the fall of '56. Harry was a minister-turned-fry cook whose watershed career move was getting fired from a Nevada church for developing an extra-professional interest in a teenage parishoner’s spiritual development.

Harry drove a Buick Riviera that had, like Harry, seen better days. Even the dashboard Jesus seemed to have lost its lust for life. A silver dollar with a hole drilled in it hung by a string from the mirror. In a letter to written Wilhelm Reich, orgone box inventor and frequent Fullerton correspondent, addressed to the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, Fullerton wrote, “It was a fine-running automotive specimen, Will, but it was no Mercury.” |

|

4. She's Driving Him Out of Her Mind

copyright Leon Fullerton She took the car keys.

She took the car key and the car. She took her flight bag. She took her flight bag, her rings, and guitar. She is leaving. She is leaving the madness behind. She is driving. She is driving him out of her mind. She said, “I will call you from San Francisco when I find a room.” He said, “Will I see you? Will I see you?” She said, “Not real soon. See, I am leaving the phantoms and mountains behind. See, I am driving. I am driving you out of my mind.” She was driving. She was driving him out of her mind. |

Celebrated visual artist Gwen Fullerton is Fullerton’s daughter by his first wife, Anastasia (Annie) del Grasso. He visited Gwen at her studio apartment in San Francisco’s Presidio in the late eighties, shortly after she had left Estes Park, Colorado, and her husband of several years.

“Why’d you walk out?” she remembers Fullerton asking her. “Was he driving you out of your mind?” “No,” Gwen said. “I was driving him out of my mind.” |

|

5. The Lawrence Factory

copyright Leon Fullerton Night after night, she kneels and says her prayers,

she kneels and says, kneels and says, kneels and says her prayers: “Lord give me strength to take me far away from here, far away, far away, far away from here.” Day after day, until the sun goes down, until the sun goes, till the sun goes, till the sun goes down, spins cotton into dollars with her sisters dressed in brown, her sisters dressed, her sisters dressed, her sisters lost and found, for they have come to labor in the land of the free, and bless the bosses’ kindness in the Lawrence factory, the Lawrence factory. Night after night, she kneels and says her prayers, she kneels and says her, kneels and says her, kneels and says her prayers: “Lord, give me wings so I can fly away from here, fly away, fly away, fly away from here, fly away, fly away, fly away from here, fly away, fly away, fly away from here, fly away, fly away, fly away from here” |

Fullerton’s aunt Sarah McCreedy emigrated from County Sligo to Massachusetts at the turn of the century with her mother and sister and worked for several years in a sprawling brick textile mill in Lawrence. She wrote in her diary (now in Gwen Fullerton's possession): "It's better than a potato famine, but that doesn't make it a Sunday picnic, does it?"

She often talked about the Lawrence Strike of 1917. It wasn't a fight she wanted to wage, but when she finally stood up to the company's bullies, it freed her soul in a way she felt needed no explanation. Later in her diary, she wrote: "I feel most badly for the children. But I was once, myself, a child laboring here. [She was sixteen when she wrote this. Ed.] Each time they strike me, spit on me, insult me or arrest me, I feel that God above is smiling down upon my head. The blessing is not that we are fighting back. The blessing is the discovering that we should, we must, we can." |

|

6. Never Going Back Again

copyright Leon Fullerton Ten miles burning 'cross the Pontchartrain,

ain't never going back again. Ten feet of rope above a burning man, ain’t never going back again. Blood weight hanging from a fever tree, ain't never going back again. Blamed and hanged, looked nothing like me, ain't never going back again. I'll tell you what but not where or when, ain’t never going back again. Maybe way up there, maybe way back then, ain’t never going back again. Nothing like a lynching on a Saturday night, ain't never going back again, to teach a hard head a little wrong from right, ain't never going back again. Ain't never going back to the Jubilee, ain't never going back again, ain’t never going back to the Tres Jolie, ain’t never going back again. Give a letter to my ma, give a dollar to my pa, ain't never going back again. Ain't never gonna rise, pray to God I never fall, ain’t never going back again. Ain’t never going back again, no, no, ain’t ever going back again. Ain’t never going back again, great God, ain't never going back again. |

In 1963, Fullerton was playing with his brother Lionel’s band, the Lake Charles Fenderbenders, on Frenchmans Street in New Orleans. Between sets, he got to talking to a bar fly with ravaged veins, an alarming facial tic, and what must have amounted to a half-carton-a-day Chesterfields habit.

His name was Vic, and — as Fullerton related to Billboard later that year, when his album Legends of the Heartland came out — Vic had killed a man twenty years back in an argument over a barmaid who worked part-time at the Tres Jolie, a bayou roadhouse that specialized beer, whiskey, and all manner of crawfish dishes. Vic never got to be a suspect. He woke up the next day blood-soaked and hung over, and learned that, well before sunrise, local vigilantes had tried, convicted, and lynched an African American transient who’d been washing the Tres Jolie's dirty dished for the past month or so. “’Why are you telling me this?’ I ask him. ‘Looking for someone to turn you in? Why not just turn yourself in?’” “Vic just laughs, hacks out a ragged Chesterfield cough, twitches, and knocks back his beer. ‘Naw,’ he says and starts waving at the bartender for a refill pronto. Says, ‘Hey, man, you could try. I done tried it myself four times. Police. DA. Ain’t but no one wants to hear it. The case was closed before it was opened.’ "That's when I figured something out. Sometimes hell is not getting caught.” |

|

7. This Is the Road

copyright Leon Fullerton This is the road, the road we are riding,

this is the road to take us home. This is the road, the road we are riding, this is the road, the road to take us - It was a flood-bound diner, wore an electric halo, vinyl coffee, fluorescent booths. The waitress was Flo - no, the waitress was Georgia. Shows what time will do to the truth. This is the road.... The jukebox rocked. Eddie Cochran was channeling God, and you asked me, “Will the rain break soon?” I said, “Flo! I mean, Virginia! A refill on the refills!” Then I said, “We’re gonna fly by the light of the moon.” This is the road.... Three long blasts and a Pete speeds past, a cross on the grill shines, tries to light the load. Some shall be calmed by the balm in Gilead, some shall rise, some shall explode. This is the road.... We pass over the Badlands, the broken heartland, hitching all night through Piedmont towns, cities black against blazing billboards, fire signs, angry sounds. This is the road, the road we are riding, this is the road to take us home. This is the road, the road we are riding, this is the road, the road to take us home. >> Out-take: An earlier rehearsal: |

|

8. Division Street

copyright Leon Fullerton Here’s to bygone friends, may we once more meet,

a wind blows down Division Street. When your hat’s in your hand, you vote with your feet, a wind blows down Division Street. Your kids gotta live, your kids gotta eat, a wind blows down Division Street. Do you take your stand? Do you taste defeat? A wind blows down Division Street. Division Street, different as night and day, Division Street, living and dying the American way. Here’s to purple mountains and amber wheat, a wind blows down Division Street. You been robbing Paul to pay off Pete, a wind blows down Division Street. It was the heat of the night, it was the night of the heat, a wind blows down Division Street. Who writes the rules don’t need to cheat, a wind blows down Division Street. Division Street, different as night and day, Division Street, living and dying the American way. |

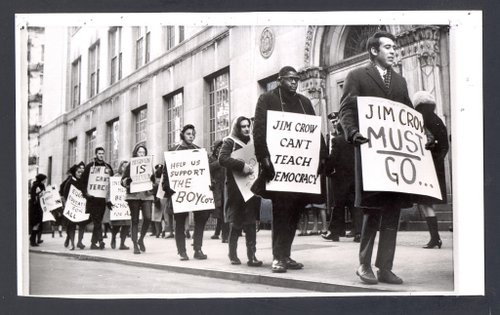

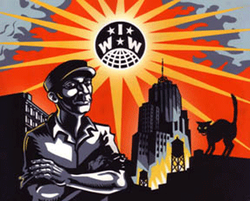

Newsman/author Studs Terkel and cowboy/mystic Fullerton first met in a bar on Division Street in Chicago in the early sixties, and they apparently enjoyed an occasional drink, sandwich, or coffee well into the eighties. The great divide between the working class and the owning class was very much on the minds of both men, and the various meanings of the street’s name were certainly not lost on either.

The Fullertons, who have always considered Leon Fullerton to be, first and foremost, a class warrior, made it the title song of their debut album. |

_______________________________________

|

9. The Mud Creek Moan

copyright Leon Fullerton (instrumental) |

As a teenager, Fullerton did occasional odd jobs at the Shady Rest Convalescent Home* in Mud Creek, Texas. It was agreeable work. But several years later, Fullerton heard stories about unsolved disappearances of patients.

To his mind, it was one thing for him to disappear, being a wayward soul at heart, prone to heedlessly heeding the open road’s sweet siren song. It was another for the geriatrically improbable to go wandering off and vanish without a trace. (Although, ironically, he would do exactly that in 2003.) The disappearances were never solved, but they seemed to run their course. A movie was made about it. In his last interview with Terry Gross, Fullerton said, “I wrote it in memory of those relegated forever to institutions everywhere. The old, the mad, the infirm, the possessed, the dispossessed, the recalcitrant, the bewildered. Joints like that are to human beings what dead letter offices are to Valentine cards.” A moody instrumental piece, it was first recorded by Brandon Iron and the Sizzlers in the mid-fifties and became a short-lived regional cross-over sensation. The Fullerton brothers used it as their theme music for their Cincinnati WOW-AM radio show, House of Wax — With “Neon” Leon and “Vinyl” Lionel. Because of that (and because it’s not as annoying as many** Fullerton tunes), we selected it for our home page music. However (and this has been a point of frequent contention and at least one threat of litigation, making clarification here appropriate), it was a contract dispute at Columbia Records, not WOW, that "meltdown in a house of wax" referred to when, 25 years later, Fullerton penned*** “Next Time I’m In LA.” __________ * Popularized in the '90s docudrama Bubba Ho-Tep. ** But who's counting? *** Or penciled.**** ****Or crayoned. |

|

10. Laika's Lament

copyright Leon Fullerton (instrumental) |

1957 was good year for space racing but a bad year for animals' rights. Russian "space dog" Laika's one-way ticket to immortality came at the price of oblivion.

Although Laika died within hours of launch, probably because of a mechanical failure of the rocket, the Russian news apparatus led the world's people to believe that she survived for six days before - as planned - she ran out of oxygen. Fullerton spent much of those six nights awake imagining the stray Muscovite mutt's tragic and unearned predicament. As a champion of underdogs across the United States, the story helped cement Fullerton's conviction that no nation, creed, or ideology has a patent on oppression. It is, he wrote in the liner notes of Boca la Luna, "an equal opportunity destroyer," and added, "Even a workers' paradise is no Eden." He composed "Laika's Lament" as a reminder of what he called "the paltry, arbitrary fates of strays, mutts, outcasts, cast-aways, and cast-offs everywhere." |

|

11. Cora, Cora

copyright Leon Fullerton Cora, Cora, where you been so long?

Cora, Cora, where you been so long? I mashed your favorite whiskey and sang your favorite song. Cora, where you been so long? Cora, Cora, where'd you spend the night? Cora, Cora, where'd you spend the night? First I dragged the river, then I saw the light. Cora, where'd you spend the night? Cora, Cora, hand me down my walking cane. Cora, Cora, hand me down my walking cane. Why should I stand here freezing when I can walk out in the rain? Cora, hand me down my walking cane. Cora, Cora, I will miss you when I'm gone. Cora, Cora, I will miss you when I'm gone. You sing like Aunt Molly Jackson, and you play like Uncle John. Cora, I will miss you when I'm gone. |

Brandon Ratajack, leader of Brandon Iron & The Sizzlers, broke up the band when his girlfriend, fiddler, and lead singer Cora Mae Endicott Pamplemousse broke up with him, thus terminating another ill-fated chapter in the many-volume collection of Leon Fullerton's failed musical enterprises.

The fight wasn't over any of the Big Three - infidelity, money, or sobriety. Cora felt she was doing the heavy lifting for the band and wanted it named after her - Cora deApple, Cora Cedin, Cora something, anything. Brandon felt that since he had built the band and got the gigs and since the band had a following, it was out of the question. He was right about the first part. He'd pulled the band together out of thin air, and he worked the chitlin circuit hard for gigs. But any following was mostly in his extravagant imagination. The band was good, but as Leon Fullerton put it, "A household word? We weren't even a household punctuation mark. Hell. An asterisk in a footnote in the appendix of a doctoral dissertation on accidents involving defective Missouri gumball machines got more attention than the Sizzlers ever did." |

|

12. Dakota (The Wobbly's Song)

copyright Leon Fullerton The bosses drove me from Dakota,

I was lucky just leave be alive. Only had but one regret: no change to say goodbye. And so began my wanderings, to walk this weary land, every town and hobo jungle, with a bindle in my hand. I've rode the Bangor & Aroostook, I've road the Wabash Cannonball, I've rode the Detroit Lightning - dear God, I've rode them all, and I'll surely make it home to you, for what they say is true: There ain't no telling what a good Dakota boy might do. I sat down at GM, walked the Ford Rouge picket line, picked grapes for the Party, drank deep of that fine red wine. The Badlands and the flatlands sing a siren's song to me, four stone-cold presidents laugh my name and sing a song about a gallows tree. But the smell of early harvest, the feel of an old flop hat, the taste of a truckstop coffee, they always take me back. I was never bound for glory, I was always bound for you, and there ain't no telling what a good Dakota boy might do. No there ain't no telling what a good Dakota boy might do. No, there ain't no telling what a good Dakota boy might do, what a good Dakota boy might do. |

"Dakota" is Fulleton's last known song, written in the rehab hospital from which, just a few days later, he escaped.

His room was semi-private, which Fullerton defined as not private at all. His roommate, Elwell J. Smoot, was a crusty old cuss grappling with the slow arrival of dimentia and the fast departure of his liver. A good twenty years Fullerton's senior, Smoot had a long and eventful trade-unionist backstory. He'd been a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (the I.W.W., a.k.a. the Wobblies), the Communist Party USA, and Congress of Industrial Organizations (the CIO). While still a teen, Smoot had involved himself in union organizing activities and come to grief with his employers in one of the Dakotas. (It was never clear to Fullerton which, but he felt confident in assuming that it wasn't where John and Yoko lived.) An arrest warrant for young Smoot on a murder charge was posted. (Smoot maintained that if he'd been able to find a courageous and pro bono lawyer, he'd have beaten the charge at a cakewalk.) So he bade his sweetheart farewell, promised to return just as soon as the back of the oligarchy was broken or the murder rap was dismissed, whichever came first, and fled by raft down the Missouri, his recent reading of Huckleberry Finn having apparently had a profound effect on him. But he never went home. He'd always intended to, he told Fullerton, but immersed in the labor struggles of the thirties first, then dogged by the murder rap he feared facing, the right moment had never presented itself. He put it off and put it off. He'd always intended to get around to it, and he still did - just as soon as his liver problem had cleared up. Fullerton had to hand it to him. Age, destitution, and infirmity hadn't dampened his enthusiasm a whit. Fullerton also noted, however, that Smoot had lost sight of several fundamentals: that young Nelly wasn't young anymore, that she had probably long since given up waiting for him, and that Smoot had no way to get to Dakota - either Dakota - to find any of that out for himself. To Smoot's capricious mind, his betrothal was a settled thing. All that was lacking, said Smoot, was "a habeas and a corpus. I just gotta get myself there, that's all. And figure out how to get her past her parents." Nelly's parents struck Fullerton as the least of Smoot's obstacles, but the old Wobbly was clear on every aspect of the topic, to his own satisfaction if not to Fullerton's. Not one to rain on a good pinko's parade, Fullerton kept his own counsel. As Fullerton wrote in an excessively long goodbye note, Smoot had instructed him thus: "Here's what you do: Write my song. Write something I can sing to Nelly. That's what you're good at. Just write me a song to tell her where I been. You can do that, can't you?" Yes, he could. But Fullertom protested that love songs weren't his department. Smoot, not one to be put off easily, pointed out the uplifting historic aspects of the proposed musical memoir and ultimately prevailed. It was surely an easy sell. Fullerton got a kick out of Smoot, and there was an attractive artistic dimension to the project as well: Fullerton had often noted that, while there are countless songs about going back to Carolina that are needlessly demure about whether they're talking about the North or South edition, he knew of not one song that blurred the distinction between North and South Dakota. An opportunity to remedy the omission was at hand. So were his Bic and notebook. He had the means, the motive, and the opportunity. The words and chords were in the spiral pad Fullerton had left on his nightstand. This and other personal effects were collected by his daughter, Gwen, when she traveled to Michigan to look for him - fruitlessly - a few days later. More notes:

- Smoot loved the song. - Gwen Fullerton ended up visiting Smoot frequently during the three months following Fullerton's disappearance that she spent in her father's Detroit apartment, during which Smoot's lease on life expired. Gwen found him as charming as she knew people outside her immediate family found Fullerton. She sang "Dakota" at his memorial service. - She was quite flattered that Smoot kept calling her Nelly. |

_______________________________________

"It isn't nice, it isn't nice,

you told us once, you told us twice,

but if that's freedom's price,

we don't mind."

Malvina Reynolds

you told us once, you told us twice,

but if that's freedom's price,

we don't mind."

Malvina Reynolds