Friends of the Fullertons:

Dreadnot

The project: Old friends and relations of Leon Fullerton have gotten together to showcase some of their favorite Neon Leon tunes. The new compact disc Good Ol' Days features many (not all!) of their favorites.

The scheme: What’s widely known about “Neon” Leon Fullerton could, at least until the release of this album, have fit the inside of a truckstop matchbook. We've produced it (a) for the sheer ever-fun-luvin' hell of it and (b) to elevate Fullerton’s star-crossed legacy to its proper place in America’s firmament of twentieth century originals.

The band: Dreadnot's artists include Fullerton's guitarist son Jasper "Jazz" Jones and former members of Fullerton's New Mexico house band, Oberon O'Blivio and the Outcasts of Samarra: Yazoo Chaz on vocals and guitar, Delmont Fullerton on dobro and mandolin, Raphael Gunn on bass, Memphis Manny on blues harp and organ, and Obie O'Blivio on percussion.

The thank-yous: A tip of the neon sombrero to our good friends the Fullertons, the Maine-based garage rockers, for their support, encouragement, and faith. Neon Leon lives thanks to them.

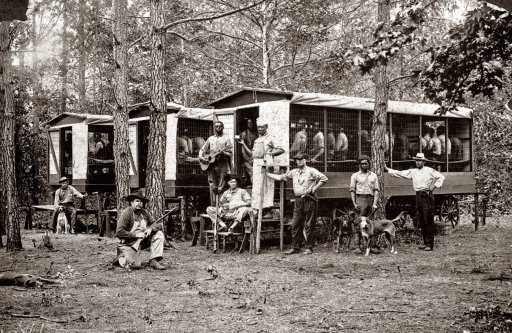

Our warm regards also go to Ginger and Beth at the Historic Adobe Museum in Ulysses, Kansas, for their kind assistance locating the Dust Bowl photos that grace the CD wallet.

And lastly and vastly, our thanks to the many people on the street whose donations to our itinerant busking made the disc a reality. Thanks to you all, Neon Leon's legacy will endure.

The small stuff: Copyright, all songs: Leon Fullerton. Audio engineering: Yazoo Chaz. Publisher: Twangri-la Records. (It don't mean a thang if it ain't got that twang!)

To order the CD: The disc is $10 plus $5 for shipping. For details on ordering one, email [email protected].

The scheme: What’s widely known about “Neon” Leon Fullerton could, at least until the release of this album, have fit the inside of a truckstop matchbook. We've produced it (a) for the sheer ever-fun-luvin' hell of it and (b) to elevate Fullerton’s star-crossed legacy to its proper place in America’s firmament of twentieth century originals.

The band: Dreadnot's artists include Fullerton's guitarist son Jasper "Jazz" Jones and former members of Fullerton's New Mexico house band, Oberon O'Blivio and the Outcasts of Samarra: Yazoo Chaz on vocals and guitar, Delmont Fullerton on dobro and mandolin, Raphael Gunn on bass, Memphis Manny on blues harp and organ, and Obie O'Blivio on percussion.

The thank-yous: A tip of the neon sombrero to our good friends the Fullertons, the Maine-based garage rockers, for their support, encouragement, and faith. Neon Leon lives thanks to them.

Our warm regards also go to Ginger and Beth at the Historic Adobe Museum in Ulysses, Kansas, for their kind assistance locating the Dust Bowl photos that grace the CD wallet.

And lastly and vastly, our thanks to the many people on the street whose donations to our itinerant busking made the disc a reality. Thanks to you all, Neon Leon's legacy will endure.

The small stuff: Copyright, all songs: Leon Fullerton. Audio engineering: Yazoo Chaz. Publisher: Twangri-la Records. (It don't mean a thang if it ain't got that twang!)

To order the CD: The disc is $10 plus $5 for shipping. For details on ordering one, email [email protected].

The song list: |

1. Gone But Not Forgot

2. Maggie Brown 3. Hard Rock Hammer 4. When the Wagon Rolls 'Round 5. Stolen Riviera 6. Sorry For Me 7. Stagger Lee 8. The Bide a Wee Inn 9. Sterno Sunrise 10. Raining All Around the World 11. Cowgirl's Lullaby 12. Just Like Tom Joad's Blues 13. Cora, Cora 14. Dakota (The Wobbly's Song) 15. The Monkey's Business 16. Delta-bound 17. Paradiseland 18. B-17 19. Laika's Lament 20. The Crossing 21. Kentucky Outlaw Nomad Biker Dude 22. Ain't She a Caution? 23. This Is the Road |

Hear them here:

|

1. Gone But Not Forgot

copyright Leon Fullerron (instrumental) |

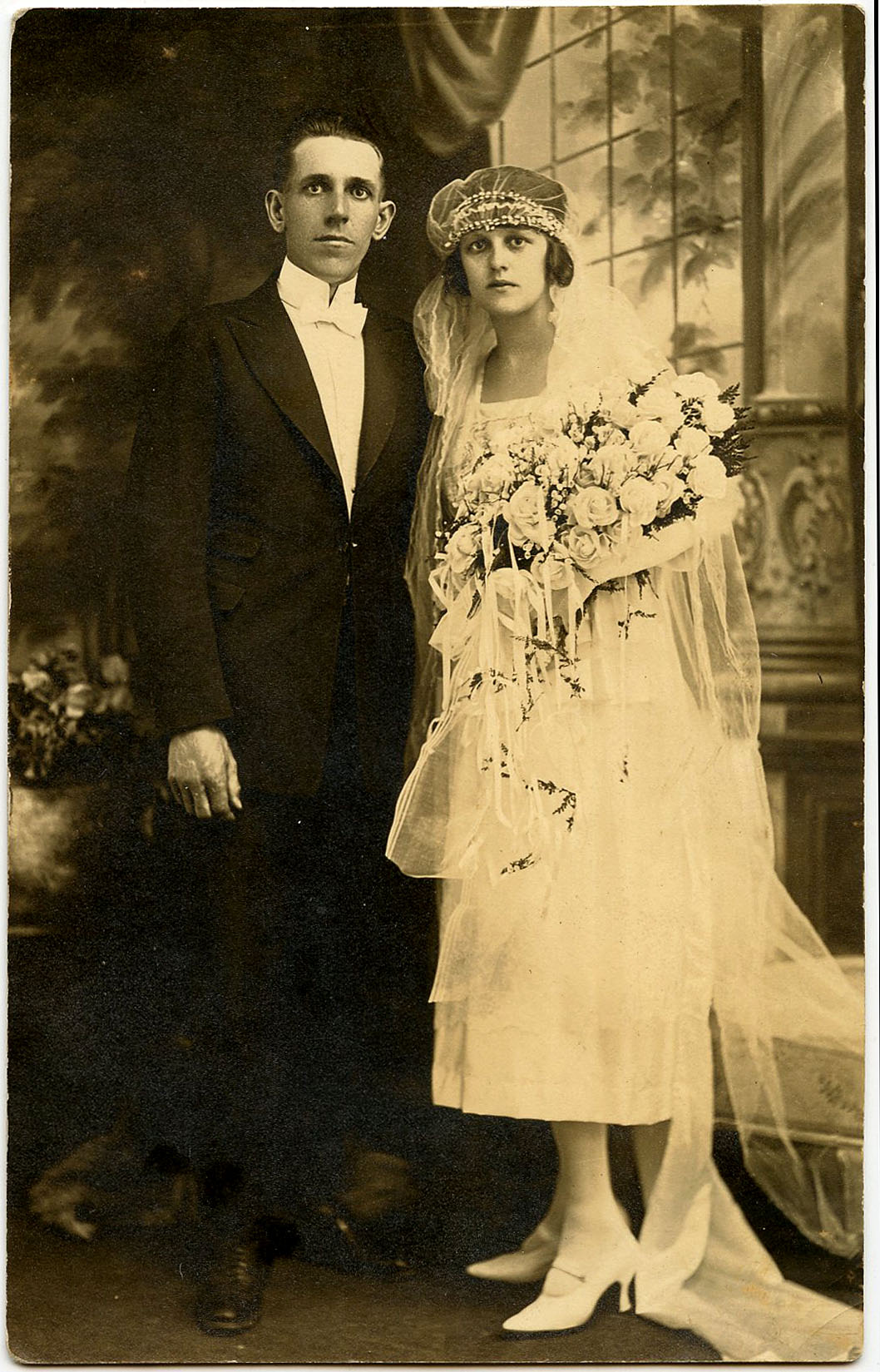

Though they could pay handsomely, Leon Fullerton seldom took wedding gigs, for reasons artistic. The bride and groom would inflict their appalling taste on him, insisting he play some Don Ho, Tony Orlando, the Eagles, worse. Which, he said, would mean he'd have to learn them. Which would mean they'd be in his head. Permanently. And there's no telling what damage they might do up there. He wasn't eager to risk it, and few couples were willing to sign the playlist veto-power condition written into his standard wedding contract.

His daughter Gwen, however, thought his motives were less about principle than practicality. As she explained it to Fullerton biographer Rex Geronimo, "Nothing stuck in Dad's head permanently. He always bragged that his musical sensibilities were superior to the average newlyweds. But the truth is, he'll play anything for anyone. His real difficulty was learning songs. He could write and sing and play them, but ask him to learn five new songs for an event and he melted down like snow in a skillet." This tune was originally entitled "Wedding March." When the happy couple divorced unamicably two months later, he renamed it "Gone But Not Forgot." |

|

2. Maggie Brown

copyright Leon Fullerton I know a gal named Maggie Brown,

she'd get all dolled up and go to town. I'd meet her there at half-past four, but she don't go to town no more. I know a gal named Maggie Black, lives in a blowed-down miner's shack. Dress her up in silk so fine, and promenade down to the company mine. I know a gal named Maggie Blue, shows the boys all what to do. Goes high-stepping Saturday night, Sunday morning sets things right. I know a gal named Maggie Green, purtiest thing you ever seen. Known far and wide throughout the land, boys kill and die for Maggie's hand. I know a gal named Maggie White, says she won't, then she says she might. Many a boy who took that bet now lives a life of grim regret. I know a gal named Maggie Red, kicked Carrie Nation smack in the head. Bottled in bond an dressed to kill, runs a ten-mile tab at the whiskey still. I know a gal named Maggie Gray, never know just what she'll say. Bought her gifts rare and devine, she said "You're kinda cute, go get in line. I know a gal named Maggie Cerise, she's more fun than a barrel of geese. Fixed her a pie and a jackalope stew, she said, "You ain't too tall, but I think you'll do." |

This song is widely remembered as one of Fullerton's favorite openers. He said: "Folks appreciate its universality. Everyone knows a Maggie Brown. Knows one or is one."

|

|

3. Hard Rock Hammer

copyright Leon Fullerton Met Jesus on a chain gang,

I said, "Lord, what have you done?" He said, "Last thing I remember, I was looking for some fun. Well, I can take them sins from you," he told me with a smile, "If you will take this hammer and go that extra mile." Take this hard rock hammer, bring it down, bring it down, take this hard rock hammer, brother, won't you bring it down? Take this hard rock hammer, bring it down, bring it down. You're a half a mile from heaven and a hundred miles, a hundred miles from town. I met the twelve apostles in a bar in San Antone. I didn't have the heart to tell them how I craved to be alone. They were headed out for supper, so I stood them for a round. They were lean, and they were thirsty, and in me a friend they'd found. Take this.... You're a thousand miles from heaven and a hundred miles, a hundred miles from town. Last time I saw God he was filling up his tank. In the chaos, I confused him for another Midland crank. I was up four hundred dollars, a six-pack, and some porn when I was finally apprehended at a car wash in Van Horn. Take this hard rock hammer . . . . You're a thousand miles from nowhere and a hundred miles, a hundred miles from town. Mary Magdalene was like a sister to me. We worked together making license plates back in '53. I said, "Why don't we crash out of here? Since when is vice a crime?" She said, "Don't matter where you live, my love, you're always serving time." Take this hard rock hammer . . . . You're half a mile from nowhere and a hundred miles, a hundred - Take this hard rock hammer . . . . You're a half a mile from nowhere and a hundred miles, a hundred miles from town. |

Fullerton’s first wife, Annie, was with Fullerton when he was on the rodeo circuit, before he hurt his back.* He was friends with a cow puncher called Red Butler. Fullerton liked Red’s impossibly sunny disposition, a contrast to Fullerton’s eternal gloom and possibly something of an palliative. Red had been on a chain gang for about a year, and to hear him tell it, no place was more fun than a chain gang.

Annie’s favorite Butler story was about a fellow prisoner who thought he was Jesus. As Pauline told Rex Geronimo, author of Fretful Life: The Life, Legend, and Legacy of "Neon" Leon Fullerton, “Jesus was always blessing anyone he could corner. Inmates, guards, warden, didn’t matter. He should’ve been in a mental hospital, but that was Texas in the fifties. Hell, it's Texas today. “Leon was always after Red to take him to Jesus to get blessed, but Red didn’t know where to find him. So Leon wrote a song, instead.” |

|

4. When the Wagon Rolls 'Round

When the wagon rolls 'round,

so I been told, can't take your lockets, can't take your gold, can't take your banjo or your fiddle and bow when the wagon rolls 'round, so I been told. When the wagon rolls 'round to collect your soul, can't take your dice or your dear bankroll, can't take your promises - oh, the lies you've told! - when the wagon rolls 'round to collect your soul. When the wagon rolls 'round, better hop on quick, it ain't gonna wait if you're tired or sick. Give up your ghost, don't try no trick. When the wagon rolls 'round, better hop on quick. When the wagon rolls 'round to cross Jordan's stream, have you made your peace? Will you be redeemed? There's a host of lost souls, oh, you can hear them scream, when the wagon rolls 'round to cross Jordan's stream. When the wagon rolls 'round, bound for glory land, have you an open heart and an open hand? Let go of blame - nothing goes as planned! - when the wagon rolls 'round bound for glory land. When the wagon rolls 'round, so I been told, can't take your lockets, can't take your gold, can't take your banjo or your fiddle and bow when the wagon rolls 'round, so I been told, when the wagon rolls 'round, so I been told. |

Long before founding the First Church of Latter Day Cowboys, which he continues to serve in abstensia as Archshaman, “Neon” Leon Fullerton was penning gospel tunes. “When the Wagon Rolls ‘Round” proved to be a sure-fire tent-rattler. In a 1980 Vidalia Vanguard review of his album Seven Ways from Sunday, he spoke extensively about his secular music:

"I’m the product of a mixed marriage. My mother was a woman, and my father was a man. There were religious differences, too. Daddy’s side was a pack of pure-D Bible belters, and they knew how to put on a revival. Those Fullertons played at lots of meetings, and they managed to get on live radio pretty often.

"Music was on Ma’s side, too, but it leaned more to popular styles, stuff you’d expect from her Judeo-Hebraic upbringing. She had a trumpeter cousin who made it big in Tin Pan Alley, Sol “Stink” Baum. A couple of Baums were cantors. I have a nephew fronting one of those apocalyptic punk outfits, Adam Baum and the Eve of Destruction. Not what you’d call a strictly sacred sound, but there’s not mistaking the lineage. "What really brought my parents together was folk music. Neither of ‘em could get enough. Carters, Almanacs, Sonny and Terry, Woody, Aunt Molly Jackson, whatever. It was their uncommon denominator. Sonny and Terry, they stopped by in Oakland a time or two. PThat six-string flattop sound has pretty much always dominated the whole family, musically." |

|

5. Stolen Riviera

copyright Leon Fullerton She was born in a desert town,

never ran with the pack. One day she stole a preacher’s car, oh, she never looked back. Some days are bright as Mojave skies, some days drown her in ocean light, some days drown her in happiness -- I hear she’s doing alright. Folks used to say: “That girl ought to find a boy and settle down, that girl’s too wild for her own damn good, that girl keeps a silver dollar in her pocket, that girl will never learn to do the way she know she should.” She learned to praise the savior in that Buick’s back seat. Jesus jumped like a hula doll, her education to complete. The preacher’d say, “Trust the Lord and the invisible hand." He said, "I’m drowning in this sea of sand. Throw me rope, I’m a family man!” Folks used to say . . . . So she left this town in the spring of aught-two, never said goodbye - had no one much to say it to. She left that Buick on a pier with a thank-you note wrapped around a silver dollar, and then she caught the last boat. Folks used to say . . . . |

A drunk named Harry picked young Fullerton up hitch-hiking from Oakland to Reno in the fall of '56. Harry was a minister-turned-fry cook whose watershed career move was getting fired from a Nevada church for developing an extra-professional interest in a teenage parishoner’s spiritual development.

Harry drove a Buick Riviera that had, like Harry, seen better days. Even the dashboard Jesus seemed to have lost its lust for life. A silver dollar with a hole drilled in it hung by a string from the mirror. In a letter to written Wilhelm Reich, orgone box inventor and frequent Fullerton correspondent, addressed to the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, Fullerton wrote, “It was a fine-running automotive specimen, Will, but it was no Mercury.” |

|

6. Sorry For Me

copyright Leon Fullerton Gambled away my money,

cheated away my wife, lost track of where I've been and where I'm going, yes, I’ve lived a fretful life. Did hard time for some unnamed friends till the good Lord set me free - so doncha feel just a little bit sorry for me? Hey, baby, feel just a little bit sorry for me. I’ve been up, I’ve been down, I’ve been side by side, I’ve been rich, I’ve been poor, I’ve let a few things slide. You play the hand that you’ve been dealt: it’s fold or raise or see - so come on baby, feel just a little bit sorry for me. Yeah, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. When I come knocking at your back door with a hobo’s howdy-do, here but for the grace of God stands a man who’s just like you. It takes a down-by-the-riverside sanctified soul to endue such misery, so come on, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. Hey, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. Doncha feel just a little bit sorry? Doncha feel just a little bit sorry? Come on, baby, feel a little bit sorry for me. |

Whenever he was in Cleveland, Fullerton liked to look up his friend Dale “Blue” Barnett and scout out a card game. The games were always for table stakes: when someone was out of money, he was out of the game. Occasionally, a player who’d lost everything would have to be ejected forcibly. One night, during an after-hours game at a bowling alley, a cleaned-out player had to be thrown out into a snow storm. The alley owner tossed out the player, followed by his coat, followed by his hat, followed by a spittoon.

The last words Fullerton heard the man shout before the owner slammed and locked the door were, “Hey! Doncha feel just a little bit sorry for me?" Fullerton himself was ejected shortly thereafter. |

|

7. Stagger Lee

copyright Leon Fullerton Billy Lyons said to Stagger Lee,

"So glad you packed your gun. On the highway to Emmaus, ran into Elvis on the run. ‘Wild Bill,’ he said, 'the life I've led could become an eternity, but I'd sooner lie down here and now than cross old Stagger Lee.' "I could not doubt He was the King, for when they rolled away the stone, all they found was a sequin leisure suit and a rhinestone black-cat bone. But still, I begged to differ, for I'm reckless, rash, and true. I said, 'One clear shot at Stagger Lee is the least that I can do.'" Stagger Lee said to Billy, as he loaded up his gun, "You shoulda listened to the King, he loves you like a son. This gin joint runs an honest game, now I’m getting called a cheat, I’ll take that brand-new Stetson hat, so pleased that we could meet!" Showdown at the hoedown, just down the road from Calvary! The boy is gonna go down, throwin' down with Stagger Lee! The whole town's got the low-down, everybody running out to see! Showdown at the hoe-down, heaven help a fool like me! Stagger Lee had a bead on Billy before Billy's gun cleared his pants, and Stagger Lee, he called the tune, and Billy commenced to dance. The first shot broke some bottles, the second broke some hearts, the rest of them broke poor Billy into a hundred parts. Elvis slipped out into the alley - no one ever saw - sashayed down Billy's house, tapped on the kitchen door. The house was dark, a woman called, "Billy where you been?" Elvis said "Billy's gone for good," that little widow said, "Come on in!" Showdown at the hoedown... |

It comforted Fullerton to know that he wasn't the only one to have seen Elvis Presley alive long after the King's go-by date went by.

But he may have held the record for quantity of sightings. The fact that he'd seen Elvis repeatedly, and always in unlikely places - cross-legged in a loin cloth atop a peak in the Sangre de Cristos, on all fours in a prison jump suit lapping milky ice water from a freshet at the foot of Mount Shasta, in an Uncle Sam outfit pumping gas in Midland, Texas, with "Elvis" embroidered in red cursive on a white oval on the breast pocket of his pump-jockey shirt, in a pewter-gray pin-striped business suit among the commuters at the Massapequa Park station of the Long Island Railroad - smoke-signaled to Fullerton a deep communion with the king of rock 'n' roll. And Fullerton the visionary knew visions. He seldom knew what they meant, but he knew they were meant for him. And meaning was of secondary interest to the musician. Experience, he believed carried its own uber-Cartesian freight: I think, therefore I am, I think. It was upon his fifth encounter with the dead Presley that Fullerton was inspired to commemorate the legendary Memphisticate in song. It was Christmas Eve, 1995, in North Saint Louis, and a sound from down the street caught Fullerton's attention: Elvis was behind the bakelite wheel of an ancient tour bus, announcing sites of interest over the geriatric vehicle's PA system. The sound quality was poor, but the voice was unmistakable. It was a special night - not just the eve of the celebration of the birth of the Prince of Peace, but the centennial of the murder of William Lyons by the pimp "Stagger" Lee Shelton. "And it was right here, the site of Bill Curtis's old saloon, a hundred years ago tonight," Presley was telling his handful of sightseers as the geriatric bus wobbled past Fullerton, "that one 'Stag' Lee Shelton murdered his way into infamy." Fullerton had come to downtown in search of a pawnshop where he could find a worthy last-minute gift or two for himself, having no one else to celebrate the holiday with that year, and Christmas Eve struck him as a peculiar time for a tour bus to be operating. He was, in fact, thoroughly lost and nowhere near a pawn shop. Compounding the moment's peculiarity, Fullerton realized that he no longer standing in modern Saint Lou (Convention Plaza to natives, upscale urban armpit to him) but transported, Scrooge-style, into the bygone Chestnut Valley red light district that had once occupied the spot. A street sign said it the corner of Morgan and Eleventh streets. Presley continued: "Shelton shot Billy Lyons dead over a hat, seizing immortality for the both of them with just one bitty bullet. Man, it took me 107 singles, 74 albums, thirty EPs, 33 movies, one meeting with Slick Dick Nixon, and simultaneous ingestion of eight controlled substances. "But I ain't complaining. Shoot, I musta died for someone's sins. And living forever ain't a bad way to die. Now, right over there on your right...." The bus rolled on into the gathering twilight, and Presley's voice faded away. And as Chestnut Valley disolved and the twentieth century returned, Fullerton was certain that he detected the swinging of a saloon door, the bark of a pistol, the rolling of a stone, and a razor whiff of sulfur and cordite on the winter air. Just as every visual artist must sooner or later paint a crucifixion, every folk singer must sing a song about Billy Lyons, Stagger Lee Shelton, a Stetson hat, and murder most graphic. Visions of pawn shops no longer dancing in his head, Fullerton knew the time had come to swallow his Skoal and make his contribution to the tradition, alone on a holy night in a sinful city, with nary a wise man in sight. Keenly aware that immortality is for the Elvises and Jesuses of the world, not for luckless transients burdened by the curse of verse, he ducked into the first door he could find that seemed conducive to song composition - not a manger or mansion, but a hotel lobby - helped himself to a pad of the establishment's stationery, and composed the ballad that he named, in respect to time-honored tradition, "Stagger Lee." |

|

8. The Bide a Wee Inn

copyright Leon Fullerton Down by Black Crater Lake

out on Highway 17, there's a stand of scruffy pine trees with some shacks stuck in between. Quebec and Alabama tags, Iowa and Dade. Kids with poison ivy chase each other in the shade. Some townies are unwinding from a hard stretch at the mill. A solid month of overtime won't start to pay this bill. Baste up on bug juice by the gallon, swill salvation by the quart at the Bide a Wee Inn cozy guest cabin court. Them old hog-riding brothers got a gleam upon their shades: up from Crystal City, down from one too many raids. The lazy crunch of gravel, ice cubes dancing in a glass tintinnabulate the murmur of the moments drifting past. A couple hours creep by, that big pink eye sinks down, music's growing louder, like a rumble from the ground. Radios are blowing hot, like sirens in the night. Someone looking for some loving, someone's cooking up a fight. A motorcycle mutters with a sychopated cough. Someone wants to get it on, someone's trying to get off, and the slamming of the screen doors in the sultry evening air punctuates the meditation of them punks in their Bel Aire. TVs are glowing bluer than a Tin Pan Alley sax: office grunts in their tank tops paying hard cash to relax. The stink of sweat is wafting from the highway to the lake. Someone is on the hustle, someone else is on the make. There's a radio evangelist in cabin number nine with a sacrament more potent than the angel is divine. Someone detonates a pop-top, someone's yanking someone's chain, someone's dog has found some road meat, someone's ex has hitched to Maine. There's a glint of summer lightning in the mountains 'cross the lake, and the sullen moan of thunder, and a chill no one can shake. There is no wind in the willows, but a prophesy of rain, like a sudden premonition, like the fear you can't explain. And night, it settles slowly, just like ether on the brain, and one by one, the lights snuff out, just one or two remain. A diesel in the distance rumbles furtively as sin and spurns the winking neon of the Bide a Wee Inn. |

”Must've been maybe in the Dakotas or Minnesota or the flat part of Montana, the Missouri Breaks, I dunno. My van broke down near one of those cabin resorts and I spent a couple of nights there. Fixed some screen doors and some plumbing and whatnot and got some meals out of it. Slept in the van. There was no vacancy.

“The place jumped. Middle of nowhere, folks having a great time. Cookouts, hammocks, kids playing ball, beer disappearing like truth on tax day. The song is just sort of a bunch of snapshots. Always been fond of it. It’s a crowd-pleaser. Everyone knows what I’m talking about.” So wrote Fullerton in his unfinished memoir, Ugly Roomer. New York Daily News music critic Lillian Roxon, however, had a different take on the 1980 tune: “It’s not punk. It’s not New Wave. It’s closer to rap than anything else on the airwaves today. It takes up where Woody Guthrie’s ‘Talking Blues’ leaves off — and that left off a long time ago. Whatever the going style, we can rely on ‘Neon’ Leon to hoist the Jolly Roger and ram it amidship.” Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers took the long view: “Fullerton’s body of work is a sort of an Atheist’s Bible set to the beat of a vanishing America. Like most of his songs, once you start making substitutions here and there, it's impossible stop. Make his lake the Sea of Galilee and you begin to imagine a Breugelian landscape, an alternate Bible story teaming with Pharisees and Moabites and false prophets and sinners and saints. “Diesel exhaust is Fullerton’s holy smoke. Saints drive his tractor trailers. His angels drive motorcycles. His sinners drive cars: their exhaust is our exhausted store of lies, deceptions, and alibis. Radios are heaven, TVs are hell, and barrooms are the big waiting room in between. “By denying God, Fullerton forces the burden of holiness on the rest of us — what Mark Twain, one of Fullerton’s heroes, called ‘the damned human race.’ If Jesus died for our sins, Fullerton is out there living for them.” Fullerton’s daughter Gwen, who keeps clippings about her father in a Buster Brown shoebox, said when we probed her about Roxon’s and Travers’ comments, “It’s a good song, if you go in for that retro country bluesy twang-banger post-folk, pre-'alt' thing. Roxon nailed him — not in the biblical sense. Dad’s a pirate, all right. But if Travers really wants to understand him, he needs to dip less into the Bible and more into whatever stash of psycho-active joy juice accommodates a latter-century hip-wa-zee lifestyle. And a liquor cabinet. And if he really wants to do it Dad's way, it'll be anyone’s booze but his own.” |

|

9. Sterno Sunrise

copyright Leon Fullerton (instrumental) |

Inspired by a popular seventies Eagles song and a popular seventies cocktail. From Fullerton's unfinished and unpublished cookbook of hobo cuisine, Vagabond's Viands: Vital Vittles for the Vagrant, Flagrant, and Fragrant:

Sterno Sunrise Ingredients:

Serve chilled. Or put a coat on. Serves nobody. |

|

10. Raining All Around the World

copyright Leon Fullerton I said, "It's raining down hard,

but it won't last long, unless I immortalize it in my next hit song." She said, "This rain ain't no metaphor, it's just plain wet, shows how dumb you blues boys get." It's blowing like a bastard, fulminating like the gods, it's freezing like the devil forgot to count the odds, and it's rain, rain, raining all around the world, and it's rain rain rain rain raining all around the world, and it's rain, rain, raining all around the world, and it's rain rain rain rain raining all around the world. Voices shall be shattered by the madness of the storm, I'd wear out another Roget's, but it isn't proper form. She said, "I only came to see you to give you back your ring." I said, "That's such a tired lyric, give me something I can sing!" So she threw it, but she missed, so I knew she really cared. If she ever pulls a trigger, got no reason to be scared, except it's rain, rain, raining all around the world.... |

Fullerton's fourth wife, Helena Troy, was a fallen English major holed up in the Chicago office of a grimly over-extended music publishing concern. Until Fullerton, she'd mostly dated over-extended musicians and and over-extended music business people, and but her attraction a pagan cowpuncher fifteen years her senior was unusual. And sort of a kick.

She eventually realized what she should have know all along: that musicians were all pretty much the same in the dark - dreamers too distracted by the rhymes and melodies zinging around their skulls to be much use for anything profitable. But by the time she'd figured it out, it was too late: they were already married. The trip to Vegas had been unforgettable, what she could remember of it, but when, six months after the Bellagio, she heard herself saying exactly the words she'd said to four men before Fullerton - "You love that guitar more than you love me" - she realized it was time to split.* She didn't actually throw the ring at Fullerton - that was poetic license on his part: its fictional trajectory was an apt metaphor for the arc of their marriage. And if there was one thing marriage to Fullerton had taught her, it was the uselessness of metaphor. __________ * A casualty of the twenty-first century creative writing pandemic, originality mattered inordinately to her. Had she known that an estimated 42 million lovers (almost all women, which would have really set her feathers afire) had said those same words way before they sprang to her Fullerton-entrancing lips. |

|

11. Cowgirl's Lullaby

copyright Leon Fullerton “Yippee kiy-oh,” the coyotes sing

when the moon goes gliding by. Was that a moony coyote crooning a tune or the cowgirl’s lullaby? A sweet breeze whispers in the aspen trees. in the shadows, green leaves sigh. Was that the whispering wind a-calling or the cowgirl’s lullaby? She twirls a pearly six-gun to catch the bandits on the trail, she strums a Spanish six-string to rock the bandits to sleep in jail. She can make a bobcat take its nap and a bobcat be polite, and she will sing the cowgirl’s lullaby when she tucks the hands in tonight. There’s a handsome wrangler sings “Home on the Range,” he’ll be home from the range by and by. Was that “Give me a home” you heard just now or the cowgirl’s lullaby?” There’s a handsome wrangler sings “Home on the Range,” you can bet he’ll be home by and by. Was that “Give me a home” you heard just now or the cowgirl’s lullaby? |

Traveling through the San Luis valley in southern Colorado on tour with Tanya Hyde and the Leatherettes in 1963, Fullerton tipped his hat to a young woman sitting in front of the sheriff's office. She was Travis-picking a flat-top guitar and struck up some chat.

"You spin a colorful brand of yarn, stranger," she said, "but I'm bespoke." She held out her engagement ring for his edification, her hair drifting to one side, to reveal the badge on her vest. "Wouldn't be surprised if you were a mite bespoke, yourself," she added, returning to her finger-picking. He allowed that we was, and more than somewhat. Her beau, she told him, was a local ranch hand. They compared a few notes and agreed that they were two of the luckiest guit-pickers in the world - even if Fullerton Wasn't lucky that day. Fullerton wrote the song with his daughter Gwen in mind and recorded it while still on tour. Within a few months, the song became a minor favorite on the Chuck Wagon Network. Soon after, Fullerton was surprised to receive a phonograph record - the kind you used to be able to make in a coin-op boot - of the song, sung, played, and mailed by the sheriff. “Usually I do something to get put in jail and wish I hadn’t,” he said in the Crawdaddy interview. “That was one time I didn’t and wish I had.” "Cowboy's Lullaby" remains Gwen's favorite. |

|

12. Just Like Tom Joad's Blues

copyright Leon Fullerton The only home you’ve known is gone,

vanished in the dust. You thought the Oklahoma dirt was one thing you could trust. The highway teems with pilgrims once your neighbors and your friends. Another chapter closes, but the story never ends. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’re gonna roll, roll, roll to the promised land. You’ve got enough provisions to get you ‘cross the plain, to keep this old truck running just takes two hands and a brain. You can keep your family by you Lord only knows how long. You never were too lucky, but you were always plenty strong. You’re gonna.... The few, they live like pharaohs, the many build their tombs, monuments to hungry pride, heirless, empty rooms. You wander in the desert now, but you shall build again, the power in you vested by decree of mice and men. You’re gonna.... |

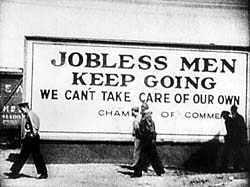

In 1940, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie saw The Grapes of Wrath and rushed out of the theater to find a typewriter (a twentieth century apparatus combining the functionality of a keyboard and printer while foregoing the expense and inconvenience of electricity).

Guthrie stayed up all night typing, singing, and strumming, aided and abetted by a jug of non-union wine. The first time the young and unforgivably cocky Leon Fullerton heard the resulting song, he was unimpressed. He wrote in his journal that it sounded: “like it was written by a boozed-up sleepwalker.” Fullerton wrote to Gutherie: “Sleep-writing and you are a match made elsewhere than in heaven, Woodrow. I’ve enclosed what I humbly submit is a tune that hits the nail a little squarer on the head.” He enclosed words and chords. Critics, of course, have unanimously disagreed with Fullerton’s estimation. Folklorists consider “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” which appears on Gutherie’s Dust Bowl Ballads (Vanguard), a masterwork. Gutherie, however, was far from offended by the young upstart. He promptly replied: “Keep kickin’ up the dust, kid. That’s how they make mountains.” Beneath his signature was a drawing of a little boy in a twenty-gallon hat kicking dust into a pile three times his size. Many years later, an older-if-not-wiser Fullerton conceded to biographer Rex Geronimo that no one knew more about dust than Guthrie. |

|

13. Cora, Cora

copyright Leon Fullerton Cora, Cora, where you been so long?

Cora, Cora, where you been so long? I mashed your favorite whiskey and sang your favorite song. Cora, where you been so long? Cora, Cora, where'd you spend the night? Cora, Cora, where'd you spend the night? First I dragged the river, then I saw the light. Cora, where'd you spend the night? Cora, Cora, hand me down my walking cane. Cora, Cora, hand me down my walking cane. Why should I stand here freezing when I can walk out in the rain? Cora, hand me down my walking cane. Cora, Cora, I will miss you when I'm gone. Cora, Cora, I will miss you when I'm gone. You sing like Aunt Molly Jackson, and you play like Uncle John. Cora, I will miss you when I'm gone. |

Brandon Ratajack, leader of Brandon Iron & The Sizzlers, broke up the band when his girlfriend, fiddler, and lead singer Cora Mae Endicott Pamplemousse broke up with him, thus terminating another ill-fated chapter in the many-volume collection of Leon Fullerton's failed musical enterprises.

The fight wasn't over any of the Big Three - infidelity, money, or sobriety. Cora felt she was doing the heavy lifting for the band and wanted it named after her - Cora deApple, Cora Cedin, Cora something, anything. Brandon felt that since he had built the band and got the gigs and since the band had a following, it was out of the question. He was right about the first part. He'd pulled the band together out of thin air, and he worked the chitlin circuit hard for gigs. But any following was mostly in his extravagant imagination. The band was good, but as Leon Fullerton put it, "A household word? We weren't even a household punctuation mark. Hell. An asterisk in a footnote in the appendix of a doctoral dissertation on accidents involving defective Missouri gumball machines got more attention than the Sizzlers ever did." |

|

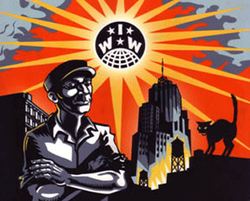

14. Dakota (The Wobbly's Song)

copyright Leon Fullerton The bosses drove me from Dakota,

I was lucky just leave be alive. Only had but one regret: no change to say goodbye. And so began my wanderings, to walk this weary land, every town and hobo jungle, with a bindle in my hand. I've rode the Bangor & Aroostook, I've road the Wabash Cannonball, I've rode the Detroit Lightning - dear God, I've rode them all, and I'll surely make it home to you, for what they say is true: There ain't no telling what a good Dakota boy might do. I sat down at GM, walked the Ford Rouge picket line, picked grapes for the Party, drank deep of that fine red wine. The Badlands and the flatlands sing a siren's song to me, four stone-cold presidents laugh my name and sing a song about a gallows tree. But the smell of early harvest, the feel of an old flop hat, the taste of a truckstop coffee, they always take me back. I was never bound for glory, I was always bound for you, and there ain't no telling what a good Dakota boy might do. |

"Dakota" is Fulleton's last known song, written in the rehab hospital from which, just a few days later, he escaped.

His room was semi-private, which Fullerton defined as not private at all. His roommate, Elwell J. Smoot, was a crusty old cuss grappling with the slow arrival of dimentia and the fast departure of his liver. A good twenty years Fullerton's senior, Smoot had a long and eventful trade-unionist backstory. He'd been a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (the I.W.W., a.k.a. the Wobblies), the Communist Party USA, and Congress of Industrial Organizations (the CIO). While still a teen, Smoot had involved himself in union organizing activities and come to grief with his employers in one of the Dakotas. (It was never clear to Fullerton which, but he felt confident in assuming that it wasn't where John and Yoko lived.) An arrest warrant for young Smoot on a murder charge was posted. (Smoot maintained that if he'd been able to find a courageous and pro bono lawyer, he'd have beaten the charge at a cakewalk.) So he bade his sweetheart farewell, promised to return just as soon as the back of the oligarchy was broken or the murder rap was dismissed, whichever came first, and fled by raft down the Missouri, his recent reading of Huckleberry Finn having apparently had a profound effect on him. But he never went home. He'd always intended to, he told Fullerton, but immersed in the labor struggles of the thirties first, then dogged by the murder rap he feared facing, the right moment had never presented itself. He put it off and put it off. He'd always intended to get around to it, and he still did - just as soon as his liver problem had cleared up. Fullerton had to hand it to him. Age, destitution, and infirmity hadn't dampened his enthusiasm a whit. Fullerton also noted, however, that Smoot had lost sight of several fundamentals: that young Nelly wasn't young anymore, that she had probably long since given up waiting for him, and that Smoot had no way to get to Dakota - either Dakota - to find any of that out for himself. To Smoot's capricious mind, his betrothal was a settled thing. All that was lacking, said Smoot, was "a habeas and a corpus. I just gotta get myself there, that's all. And figure out how to get her past her parents." Nelly's parents struck Fullerton as the least of Smoot's obstacles, but the old Wobbly was clear on every aspect of the topic, to his own satisfaction if not to Fullerton's. Not one to rain on a good pinko's parade, Fullerton kept his own counsel. As Fullerton wrote in an excessively long goodbye note, Smoot had instructed him thus: "Here's what you do: Write my song. Write something I can sing to Nelly. That's what you're good at. Just write me a song to tell her where I been. You can do that, can't you?" Yes, he could. But Fullertom protested that love songs weren't his department. Smoot, not one to be put off easily, pointed out the uplifting historic aspects of the proposed musical memoir and ultimately prevailed. It was surely an easy sell. Fullerton got a kick out of Smoot, and there was an attractive artistic dimension to the project as well: Fullerton had often noted that, while there are countless songs about going back to Carolina that are needlessly demure about whether they're talking about the North or South edition, he knew of not one song that blurred the distinction between North and South Dakota. An opportunity to remedy the omission was at hand. So were his Bic and notebook. He had the means, the motive, and the opportunity. The words and chords were in the spiral pad Fullerton had left on his nightstand. This and other personal effects were collected by his daughter, Gwen, when she traveled to Michigan to look for him - fruitlessly - a few days later. |

|

16. Delta-bound

copyright Leon Fullerton Hey, now, I am loop du jour, now, baby,

a loose caboose in a trackless waste. I won't be coming home no more, darling, I got me an outside line that can't be traced. My structural integrity is in jeopardy, and this magnificent facade has been atrociously defaced. Keep them cards and letters coming, folks. Who knows? Someday I might even drop you a little line. Famous last words, darling - they carved them on my chest down at the corner of Fourth and Vine, and now I get a bluesy kind of hunger, and all that jazz goes down just like vintage Ripple wine. Well, I been thinking on my feet, baby, because my head's so heavy it just keeps on sinking down - an excruciating condition, like living to be dying in this mean old neon town. Get my grip, cause I am tripping, nail my hat on tight, 'cause I sure am Delta-bound. |

Fullerton drowned his suicidal impulses in songwriting. “Delta-bound” captures the artist’s existential anguish at its most acute.

|

|

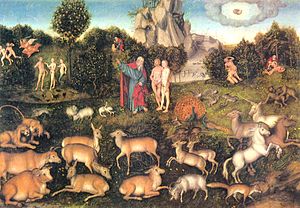

17. Paradiseland

copyright Leon Fullerton It was early Sunday morning,

Adam said to Eve, “There's so much damn temptation here-abouts, sure am glad that we believe.” Oh, honey, take my hand, woman and man were made to understand. Oh, honey, take my hand, follow me down from the Paradiseland. Eve said, “That’s a very good boy, that’s just what you’re supposed to say. It’s a covenant of the spirit -- but flesh was never made that way!” Oh, honey.... Then Eve said, “And another thing: I’m such a lucky little wife, ‘cause I got you, and I got Paradise, and I got eternal life!” Oh, honey.... Adam said, “I don’t need none of that other stuff, long as I got you, and I will abide till death do us part, no matter what you do.” Oh, honey.... Paradise is a very nice place, the Good Book says it’s so. Must take some kind of a powerful love to turn your back on the Paradise door. Oh, honey..... |

“Adam is my favorite cat in the Bible,” Fullerton once wrote to his daughter, Gwen. “He’s the guy who said, ‘Yeah, you’re my God, man, but, like, she’s my wife!’”

“Dad thought it was absolutely essential for guys to stay with their wives through thick and thin,” Gwen explained to Rex Geronimo, Fullerton’s biographer, “— as long as the wives weren’t his.” |

|

18. B-17

copyright Leon Fullerton Play B-17 one more time and I'll leave,

I can see that you're trying to close. You've turned off the lights in the restrooms, the jukebox is all that still glows. You said, "Buddy, decide where it is you reside, 'cause, buddy, you can't abide here." Play B-17 one more time and I'll leave, with a heart full of headache and a head full of whiskey and beer. It's a song 'bout a man loves a woman, and brother, I know it too well. Don't bother to turn my chair over, just leave it right here where I fell. I hope it ain't no big magilla, it's the soul's long dark night that I fear. Play B-17 one more time and I'll leave, with a head for a heartache and a heart full of whiskey and beer. |

orFullerton knew what every barfly worth his tab knows: in the secret heart of Nightworld, the pergatory of a liquor establishment is always preferable to the chaos outside its doors. The jukebox love song is always preferable to the hard-hearted light of night. Fullerton, who ushered many bars through the rites of last call, told this story of a particular bar room Bartleby — a guy who, when it was time to go home, would prefer not to. “On the jukebox of a remarkably unremarkable Cincinnati drinking establishment,” said Fullerton in the Hustler interview, “B-17 was ‘Rescue Me,’ by Fontella Bass, the one-hit wonder who hit it so far out of the park with that one, she’d managed to say it all. This poor guy - never got his name - couldn’t get enough of it. Kept saying, ‘That was our song.’ “When I realized the bartender was on the two-minute countdown to ejecting him physically, I told him, ‘No, amigo, it’s just the song you thought was your song back when you thought you and her would be together forever and ever, which you’re not going to be, or you wouldn’t be in here drunk and begging a tired bartender to play a song for you because you’ve used up all your quarters and you figure you can use it for leverage in your lame, imaginary negotiation, which won’t work, because closing time is closing time, which is why they call it closing time the whole world round.” “B-17” originally appeared on the 1964 album Nightworld. A few years later, Fullerton added a second verse that followed the first and was the same tune: Play B-17 on the record machine, the ghosts have all followed me here. They're all bellied up at the bar rail, when I give them the eye they just lear. I'm not unaquainted with spirits, be they phantoms or specters or rum. Here's a Roosevelt dime, play that song one more time, and call me a taxi or call me a son of a bum. |

|

19. Laika's Lament

copyright Leon Fullerton (instrumental) |

1957 was good year for space racing but a bad year for animals' rights. Russian "space dog" Laika's one-way ticket to immortality came at the price of oblivion.

Although Laika died within hours of launch, probably because of a mechanical failure of the rocket, the Russian news apparatus led the world's people to believe that she survived for six days before - as planned - she ran out of oxygen. Fullerton spent much of those six nights awake imagining the stray Muscovite mutt's tragic and unearned predicament. As a champion of underdogs across the United States, the story helped cement Fullerton's conviction that no nation, creed, or ideology has a patent on oppression. It is, he wrote in the liner notes of Boca la Luna, "an equal opportunity destroyer," and added, "Even a workers' paradise is no Eden." He composed "Laika's Lament" as a reminder of what he called "the paltry, arbitrary fates of strays, mutts, outcasts, cast-aways, and cast-offs everywhere." |

|

20. The Crossing

copyright Leon Fullerton I stole away from Juarez

beneath a cold coyote moon, I heard Juanita call my name, but I was sure I'd be back soon. So many promises I have made and I've as many yet to keep, and I count them like milagros as I lay me down to sleep. She wrote me on the fifth of May but I never did reply. They caught her at the crossing on the fourth day of July. She said she had to find me, but I never found out why. Now all my messages come in bottles, and the liquor tastes like lye. So many promises I have made and I've as many yet to keep, and I count them like milagros as I lay me down to sleep. |

Fullerton spent much of 1969 through 1972 volunteering with the United Farm Workers. “The Crossing” tells the story of Perce Pendleton, an unfrocked border patrol officer. Fired for one too many hydraulic lunches and haunted by memories of sabotaged love, he'd left behind a life of remorse to dedicate himself to la causa.

Pendleton lived in a trailer decorated to an OCD degree with Our Lady of Guadalupe candles, Day of the Dead artwork, and Mexican "miracle" charms. Said Fullerton: "The man was not religious by conventional standards. Took the lord's name in vain at every conceivable opportunity. Got him to a few First Church [of Later Day Cowboy] services, but he was only interested in their social aspects. "All that junk just kept him in mind of that Juarez girl. I think he needed that." |

|

21. Kentucky Nomad Outlaw Biker Dude

copyright Leon Fullerton Kentucky-bound boy

astride a great chrome dream, saw your picture in a Santa Cruz Internet laundromat cafe, flying over the Ohio, it was '66, but it looked like yesterday. A mournful woman sang a mournful song on a mournful guitar on a mournful stereo, just like she knew you, lonesome rider such a long, long, long, long, long, long time ago. Every life is a bridge, every river flows home, every song is another lost love, every destination remains unknown. Kentucky-bound boy with a skull and bones wind-combed, grease-swept, sun-stroked mad-dog hair, looking backward, beyond the picture, like the camera wasn't even there. There's songs of freedom, songs of the open road, songs of defeat, songs of the open grave. Was there freedom in a bluegrass tune, was there freedom in the song she gave? Every life is a bridge, every home is a stone, every song is another lost love, every destination remains your own. |

This 1966 photo by Danny Lyons was one of Fullerton's favorites. (A signed print of it is one of several dozen works of art currently at issue in Fullerton's estate dispute.) Lyons and Fullerton met in a variety of settings over the years - at civil rights demonstrations, at biker runs, in towns clustered along the U.S.-Mexico border - and admired one another's work.

The song was inspired by a poster of the picture Fullerton encountered at an internet laundromat cafe (the existence of which Fullerton called Exhibit A in his ongoing case against neo-hip-dom, consumer cool, web narcosis, and normative middle-class misbehavior in general) in Santa Cruz, California. He'd gone to the seaside town in 2000 to seal a product endorsement deal with Santa Cruz Guitar Company, which had expressed interest in producing a Neon Leon signature model axe. The hell was in the details, beginning with Fullerton's famously infamous punctuality disorder and ending with an exchange of the kind of words that are quickly forgotten in the wake of the sort of frenzy of embellishment native to raconteurs eager to discount their own absence when the actual words were uttered. Suffice it to say: Fullerton beat a retreat, seeking quick solace in the first sturdy cup of joe he could find, and found himself in a coffee house puzzling over an absurdly wide selection of coffees from lands familiar only to the League of Little Nations and Indiana Jones. The coffee was adequate, the ambiance ambient. A Gillian Welsh album played sadly but agreeably on the stereo, laundry sloshed in the washers and thudded in the dryers, lattes shwooshed and snorkled into patrons' mugs, keyboards clacked, a cash register clattered and beeped, and the poster of the Lyons photo, hanging in the stairwell to the upper salon, presided - a surprise visitation, right when Fullerton needed at least the ghost of a friend. He bummed a ballpoint from a barista, snatched some napkins, sat down with a cup of the house's latest designer blend (Frank Sumatra), pulled his old Gibson LG-2 out of its case (a small guitar good for traveling, the prototype for the proposed Santa Cruz model), composed "Kentucky Outlaw," played it for the Urban-Outfitted patrons, got the response "you only get when you've buttoned up one hell of a tune,"* and pronounced the trip to Santa Cruz a success. |

|

8. Ain't She a Caution

copyright Leon Fullerton I have seen the city,

where the streets are paved with light, and I have met a gal or two could make a man ignite. I could've took the high road if I'd just knowed up from down, but the path of least resistance brought me straight to Heartache Town. Ain't she a daydream, still on my mind? Ain't she a caution? Ain't she a friend of mine? It ain't her eyes that haunt me whenever I'm alone, it ain't her lips that whisper 'bout the things I might have done, it ain't the silent memory of why I chose to go to meet my own betrayal on every face in every door. Ain't she the headlights when the moon don't shine? Ain't she a caution? Ain't she a friend of mine? I know I ain't the first damn fool to leave a love behind, to throw away what matters for what I will never find, and one too many flophouse nights is more freedom than I need, so I'm lacing up my walking shoes, see where they might lead. Ain't she the jackpot, the one I left behind? Ain't she a caution? Ain't she a friend of mine? Ain't she the jackpot, the one I left behind? Ain't she a caution? Ain't she a friend of mine? |

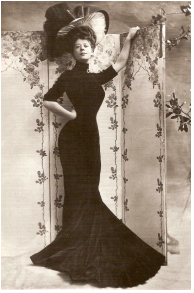

"Ain't She a Caution" was a sequel to another of Fullerron's near-hits, "Hot Springs," continuing the telling of his uncle Gustavius Gunn's 1920s walk on the wild side.

Fullerton particularly remembered his uncle's practical advice on the subject of gambling: "If you join a poker game and can't figure out who's about to get fleeced, be prepared to see a shorn sheep next time you look in the mirror." Gunn's two-month ramble earned him a black eye from Arnelle, his wife of twenty years, and a short but instructive jail term for bigamy. And it cured him of his wanderlust. Family legend has it that on Thanksgiving, 1942, in Baker, California, at the apartment the Fullertons had landed in after their Dustbowl sojourn, little Leon asked his uncle Gus what wanderlust was. Gus didn't miss a beat: "Wanda lust? It mighta been lust, but was never no Wanda had anything to do to do with it. No matter what Arnelle says." |

|

23. This Is the Road

copyright Leon Fullerton This is the road, the road we are riding,

this is the road to take us home. This is the road, the road we are riding, this is the road, the road to take us - It was a flood-bound diner, wore an electric halo, vinyl coffee, fluorescent booths. The waitress was Flo - no, the waitress was Georgia. Shows what time will do to the truth. This is the road . . . . The jukebox rocked. Eddie Cochran* was channeling God, and you asked me, “Will the rain break soon?” I said, “Flo! I mean, Virginia! A refill on the refills!” Then I said, “We’re gonna fly by the light of the moon.” This is the road . . . . Three long blasts and a Pete speeds past, a cross on the grill shines, tries to light the load. Some shall be calmed by the balm in Gilead, some shall rise, some shall explode. This is the road . . . . We pass over the Badlands, the broken heartland, hitching all night through Piedmont towns, cities black against blazing billboards, fire signs, angry sounds. This is the road, the road we are riding, this is the road to take us home. This is the road, the road we are riding, this is the road, the road to take us home. ------------- *Fullerton had been learning some Cochran guit licks around the time he recorded the song. When he performed it live, he chose the name of a recording artist on the fly. Friends and fans have reporting hearing him invoke Bashful Brother Oswald, Gary Davis, Aretha Franklin, Buddy Holly, Flaco Jimenez, Louie Jordan, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbeson, Elvis Presley, Nina Simone, Ringo Starr, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and others as God's antenna du jour. |

Fullerton was making his way through Fort Wayne, Indiana, one April night during a massive thunderstorm. He’d paid $250 for the car that afternoon, and he and Belinda Neptune, a shoe clerk he’d met in Sandusky, Ohio, and promised an eventful life, had driven it straight off a Toledo lot and into the downpour. It was late, the motels they passed all had no-vacancy signs, and the windshield wipers were turning out not to be the car’s primary selling point.

He’d just determined as much when an eighteen-wheeler came up fast behind them. “Between those headlights was a cross made of maybe a couple dozen fat green lights shining big, bigger, and biggest in my rearview,“ Fullerton recalled in the liner notes of None of Your Truck. The truck blasted past on a right-leaning curve and nearly sideswiped the car, forcing the stalwart but aging ’49 Mercury off the road. The car had to be towed out of the mud in the morning. At the Grammys later that year, 1980, Fullerton told producer Jerry Wexler, who was there as producer of born-again Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming: “Damn, I was born again when I saw that semi coming on hell for leatherette. I sent up a prayer to the dashboard deities. If it landed somewhere short of Nirvana, I ain’t complaining.” Neptune, who accompanied Fullerton to the awards show, added: "That mothertrucker had him some religion. I launched a quick prayer, myself." |